An entomologist team in Germany has gathered extensive evidence pointing towards mass extinction of flying insects. Scientists are now expressing major concerns surrounding lack of crop pollination and the future of agriculture productivity.

What is it about insects that make people slightly irritated or afraid? Their ability to fly, sting, buzz and die on the car windshield? Perhaps it is because of people’s general dislike towards insects that their huge population declines have gone unnoticed and unexplained, until now.

The story of disappearing bees was considered old news, however, a report released by a German entomologist group during October last year revealed a drastic 75 per cent decline in German insects during the past 27 years. The report includes a ‘Red List‘ compiled of extinct and endangered species and details the negative impacts of monoculture nature reserves.

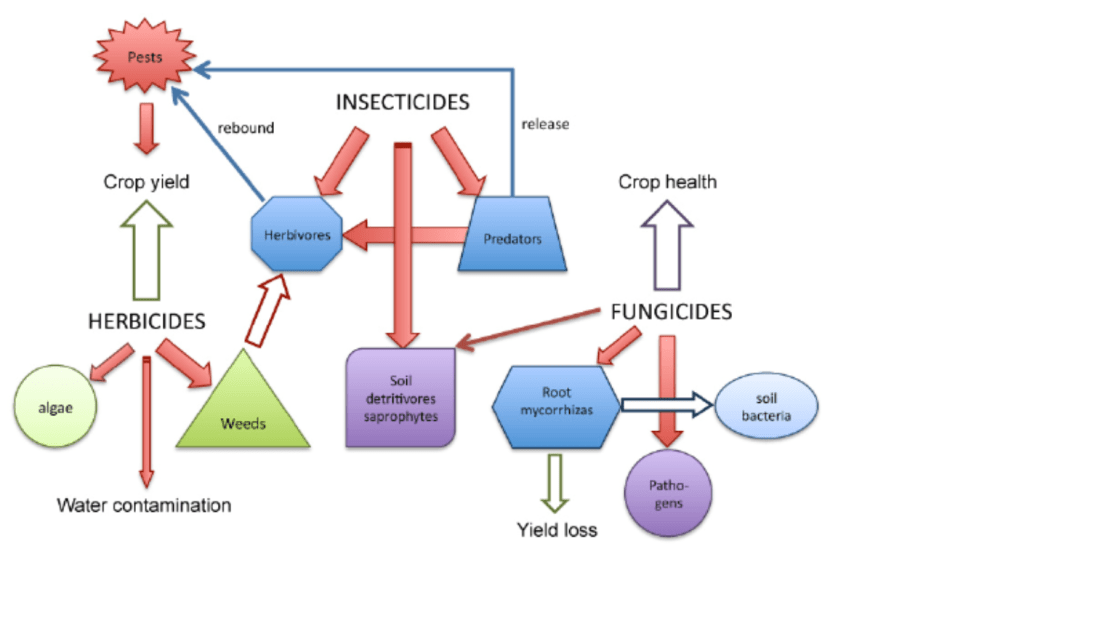

The dramatic decrease raised massive alarm bells across Europe as scientists began discussing the necessity of crop pollination and pushing for agriculture reform that is environmentally sustainable. Deforestation, fragmentation, urbanization, and agricultural conversion are all considered leading factors, however, most of the research points towards the widespread use of pesticides in the agriculture business and habitat destruction.

“In central Europe, you will have this intensive land use and agriculture,

with pesticides, with monocultures everywhere so what we need is nature reserves, which are managed perfectly, without pesticides,” states Krefeld independent researcher and insect ecology expert, Dr Martin Sorg.

“So for us, our first priority is the optimal land management of nature reserves as isolated places but they have to manage these isolated places perfectly. We don’t want to get rid of agriculture but we need a different kind of agriculture, inside and near the reserves. If not then it goes away and we go further into carelessness,” he says.

Martin explains that the immediate problem is species extinction within certain areas. The loss of only biomass of non-endangered species may leave room for possible compensation in the future however the loss of total species in a region creates more permanent damage, where a species may be completely lost because they are specifically adapted to a regional climate. Replacing a species becomes almost impossible because each insect type has already adapted to a specific agricultural area.

“When one species dies out it creates consequences for others and we don’t have enough information about what happens inside of these networks. There are more than 33,000 species of insects in Germany and for most of these we don’t have enough information to calculate how endangered they are, so in that red list, there is only a limited number of insect species that we are aware are endangered. If there is a special habitat or have habitats with a history that dates back many years then that habitat has to be managed perfectly,” stresses Dr Sorg.

So what does this mean for the agricultural industry?

The “invisible” link

The Krefeld team refuses to label one overall impact that has caused the rapid decline found in their studies, stating that “many theories could be possible at this stage”.

“We have a large number of impacts on insects in our landscapes and we have not been able to focus on one specific impact so far because we can’t link it directly to pesticide use. It’s like a cornerstone, which has been formed now for further research into different topics. Ecotoxicologists can now place more focus on one species and try to see if how, for instance, a pesticide might have an impact on one specific species in the field but this is just a further question of research,” says Krefeld member and bug specialist Thomas Hörren.

Insect custodian at the Berlin Natural History Museum, Dr Jürgen Deckert disagrees stating that there is enough data available to clearly demonstrate the causes.

“In general, the loss of biodiversity is caused by the use of pesticides, nitrification, and habitat loss. It is everywhere the same, but probably with some local differences in the amount of the factors. You need no scientific research to prove the decrease in arthropod and vertebrates. You only have to look at the data: The area with maize and rapeseed fields is much larger than some decades before in Germany. These areas have no space for diversity and most of the forests are far away from natural conditions,” says Dr Deckert.

German minister for the environment, Svenja Schulze (SPD), has also spoken out against excessive use of pesticides and recommended the moderate use of both pesticides and herbicides. After being newly elected in Schulze stated, “we need a full exit from glyphosate during this legislative period. Glyphosate kills everything that is green, depriving insects of their food source.”

The Federal Agency for Nature Conservation also released a follow-up report which stated that loss of habitat and pollutants were the main cause of extinct or endangered species mentioned on the Red List.

Dutch Botanist and ecologist specialist Professor Hans de Kroon complimented the progress made through public acknowledgement and awareness since the release of the Krefeld report.

“Interestingly, what you see in Germany and certainly also in the Netherlands is there’s now sort of a common understanding that something needs to change. This is a development of big concern and it’s perhaps too early to tell but it seems that we’re really in a transition period that we’ve got to change things in the landscape. Yeah, although environmentalists have been urging the need for this for a long time. Instead of having discussions amongst ourselves, these are now discussions which are done in parliament, on the radio, television, and major newspapers. That is really a big change,” he says.

In 1996 French beekeepers were the first to complain about their bees dying and it took 20 years really for that news to become mainstream. Wildlife declines are universal and sadly the rest of the world is lagging behind Europe and isn’t taking any action, including the US, which is a massive user of pesticides. In those countries, the fight is still going on between politicians and environmentalists arguing about what should or needs to be done.

Fortunately, when the Krefeld insect enthusiasts banned together in the early 1980’s to share their passion for entomology, they also began counting the insects and experimenting with biomass measuring. Although they ended up discovering an alarming decline in bees in their area, their work led to Europes only long-term insect dataset which has now prompted further biomass measurement outside of Germany.

Pesticides V Pollinators and what they mean for the economy

It’s no secret that bees play a crucial role in plant pollination. According to a study by Michigan University, “one out of every three bites of food is made possible by bees and other pollinators with honeybees.” This means humans are reliant on bees and pollination for an equivalent of one-third of all food production, adding up a worldwide total of 260billion euros each year.

Compared to pollinators, neonicotinoids are the most used class of pesticides in the world, affecting insects’ nervous systems. Used as a pest deterrent, the chemical can be sprayed or used as a ‘seed coater’ however over half of the neonicotinoid dose ends up in the earth and roughly 20 per cent ends up on the crops.

Peter Neumann, chair of the Institute of Bee Health in Bern University, stated in his 2015 EASAC report that pollination loss in Europe has ccost€14.6 billion thus far.

The report goes on to announce further costs of €91 billion annually worldwide due to the destruction of natural predators such as spiders and €22.75 billion in soil damage. Italy was one of the first to ban neonicotinoid seed treatment in 2008, due to pollination impacts.

During 2013 the EU’s Food Safety Agency (EFSA) found three nicotinoid substances clothianidin, imidacloprid, and thiamethoxam linked to a decline in bee populations. During May earlier this year, all three neonicotinoids were banned after the Commission proposed stricter regulations.

Professor of biology and ecology expert Dave Goulson criticised the lack of definitive progress made by the EU, reiterating the ability for another harmful chemical to replace the newly banned neonicotinoids, ultimately nulling the changes made in May earlier this year.

“I’m not overly optimistic with current progress, I must admit there hasn’t really been any international initiative launched or is being planned that is really going to tackle these issues. History suggests we keep failing to filter out the harmful chemicals during the registration process of pesticides. There are always some unanticipated negative consequences of their use, which usually takes 10-20 years to fully recognise with the GDP and the neonicotinoids.

“If we carry on with industrial farming with heavy reliance on pesticides then a ban on 3 of the 500 or so pesticides available in the EU then we’re not going to make much difference I suspect. There really is no joined-up plan to address these problems and they are enormous problems,” he says.

The German Pesticide Action Network (PAN) revealed that the sale of fertilizers and pesticides in Germany between 1994 and 2015 have risen to over 40,000 tonnes. Additionally, a study in the journal Arthropod-Plant Interactions showed neonicotinoid pesticides had long-term negative effects on crops because they harmed the pollinators that fed off them.

“People don’t seem to believe that there are other viable alternatives. I don’t think that’s true I think there are perfectly viable alternatives but they’re not in the interest to promote anything that looks to reduce pesticides and fertilizers and so on because its immediately going to hit the bottom line of some very powerful companies, so its in their very best interest to prevent those things from ever happening,” says Professor Goulson.

Despite wide criticisms that Governments are not taking immediate action in relation to nature conservation, there are some small projects attempting to make a difference by conducting sustainable farming experiments. Agri Adapt is an example of one of these initiatives.

“Our AgriAdapt project is focused on a sustainable adaptation of farms to climate change. For this our European project partnership has developed a methodology to assess the vulnerability of farms (we call it climate change check). On the base of the assessments results we create – together with the farmer – an adaptation action plan. Currently, we do this on 126 pilot farms in Spain, France, Germany and Estonia,” explains Patrick Tröstchler from the German branch of the Agriadapt organisation.

We have a long-term project in close cooperation with REWE Group (Western Buying Co-operatives Auditing Association) and the fruit farmers at Lake Constance. We started in 2010 and the 2017 wild bee-monitoring showed some very positive enhancement regarding the stabilisation wild bee populations and species,” says Patrick.

Climate change cop out?

Another explanation for insect decline discussed by environmentalists are the diverse effects of climate change. Energy transition from wind farms, biogas plants and large solar collector fields are also linked with land consumption. “The wind wheels are killing many birds, bats and insects, ” reveals insect custodian Dr Deckert.

He claims that these technical methods connected with energy transition will not induce a significant reduction of carbon dioxide and will not stop the climatic change, but will destroy large parts of the landscape and semi-natural habitats in Germany.

“Now the protection of nature is subordinated to the noble aim to fight against the climate change. Everybody see that as a priority, under this circumstances the energy transition comes first, then come the insects and birds. It is a complex and difficult issue and influenced by ideology and incompetence of politicians as well of several active environmentalists. People see the loss of biodiversity with some fear, but the fear of climatic change is much higher,” he says.

However, in their report, the Krefeld team note that linking the impacts that climate change and intensive farming have on agriculture ecology is not straightforward nor scientifically possible at this stage. Professor Kroon agrees, stating that:

“To compare the effects of intensive farming and climate change impacts…It is like comparing apples and oranges. I mean, climate change is actually a major trend of a phenomenal nature. I think we’re all very much concerned about this decline in nature reserves that are all by themselves and well managed. There’s apparently nothing wrong with it. And yet, we cannot sustain primal insect populations. Now, that is really token. That is really something, very seriously. So, perhaps the effects over-agriculture have been more devastating than we thought they already were and this is the time to do something about it,” he says.

He remains optimistic about reversing some of the damage that has been done by both climate change and intensive farming.

“The insects, in particular, are very resilient, obviously we’re doing something very wrong, but if we do the right things, roughly thinking we know what the right things are, we can get them back for sure,” he says.

Although the majority of farmers are hesitant in making the switch away from pesticides towards organic agricultural methods, some have already noticed insect decline on their properties and have implemented sustainable practices that combat both climate change and insect decline.

One of those farmers is Mr Henrich Rülfing, who made the switch in 2003.

“We switched the challenge of keeping livestock on the Hog [farm] to organic farming guidelines, cultivating it on the field with weeds and churns. As a rule, yields without pesticide use are around 50 – 70 per cent. However, monetary returns are generally higher despite lower yields. I no longer have to tell anyone that you need pesticides in agriculture,” he says.

“We have many more insects and birds here than anywhere else in the area. The Krefeld entomologists measured that with us. We are much better off because we just do not have any more exposure to pesticide drifting. However, there is a great industrial interest in the sale of fertilizer and spraying. As well as biogas and manure technology and stable engineering…the farmers’ association presidents sit on the supervisory board of the selling [pesticide/herbicide] companies. The pressure between farmers and competition among each other is very large so you get kicked out when you go eco-friendly,” he explains.

The pressure on farmers to made sudden changes to the traditional agricultural practices they are used to is a cause for slow progression.

“We used to have government-funded advisors that went around farms but they’ve all gone now due to government cuts and so on. Now the ecologists from whom farmers get their advice mostly work on commission for pesticide companies. So id love to see some independent support and help for farmers to encourage them to use fewer pesticides and find more sustainable ways of farming, rather than them getting all of their advice from companies,” says Professor Goulson.

“Farmers are the subjects of pretty heavy lobbying themselves against the removal of pesticides, the agrochemical industry and so on. They often are very defensive and when someone like me comes along and says the current farming system is damaging the environment, it’s wiping out bees and insects and is damaging the forestation etc., they tend to get defensive and say ‘well we need to feed the world what would you do without us’ kind of thing,” he says.

Marketing researchers are now looking into what are the driving forces keeping both the public actively involved in sustainable living. Farmers are interested in knowing consumer concerns, especially before taking what they consider to be an economic risk by switching agricultural methods.

Professor Kroon explains how crucial public awareness will be in the future if Germany (and the whole of Europe) are to see the long-term effects. “It’s very important that local communities and other governmental organizations involved are making sure that these changes are really sustainable. That is absolutely a challenge that is already showing at the horizon,” says Professor Kroon.

Consumer fear: “I can’t afford organic”

Farming initiatives are expected to prompt consumer changes. The largest challenge is price competition.

“You often come across the argument that organic or local food is more expensive if its produced by small-scale producers and the people cant afford it. I kind of think that’s nonsense because if you look at the proportion of income that people spend on food these days it’s absolutely minuscule compared to historical figures. In the UK present people spend about 8% of their income on food, 100 years ago it was 50%. So when people say they can’t afford to buy a bag of organic carrots I think, well most of you can. I’m sure there are a few people facing severe poverty who can’t afford it,” says Professor Goulson

“But most of us choose to spend very little on food and we’ve become so used to super cheap, bulk produced, factory farmed food and we now expect to be able to buy a litre of milk for forty pence and that’s kind of daft because we should be willing to pay more for food that’s produced in more sustainable ways,” says Professor Goulson.

“That will be a major thing and that all by itself should not take too much time. And what you see is that farmers are extremely frustrated because there’s a prospect of a certain subsidy or certain regulations being implemented. They invest in their farm and then say three years later, the system is changed. One of the deal breakers is also trying to convince the farmers as well, to make what is probably considered a drastic change to their current methods. There’s an interplay between what’s happening with the farmers and with the public opinion -both influence the other,” he says.

An agroecology farming future?

New agricultural farming strategies are being tested and so far are predicted to not only increase annual yields but will group and grow different products close together so that when harvest occurs, insects may easily rotate to other squares or lines of various crops. Compared to previous methods where crops were planted and harvested by the hectare, this new method will cause significantly less strain on biomass quality in agricultural fields.

Evidence suggests that small-scale mixed horticulture is most productive. Things like agroforestry and permaculture. Growing perennial crops and annual crops in small patches or in rows where they are mixed up and you can get multiple harvests from the same patch of land, which can be producing 10 or 15 crops essentially and they are all grown alongside each other. It’s a lot more labour intensive but its much more productive in terms of the amount of food produced per hectare.

If you compare this method to conventional big field single crops, surprisingly, they don’t actually produce that much food. Wheat, the biggest crop in Europe roughly produces about 10 tonnes per hectare. Compared to someone who is just growing vegetable in his or her own garden or something else small scale, a civilian can get about 35 tonnes per hectare without using any pesticides at all which makes one wonder why we’re doing so much wheat growing.

By shifting back to smaller farms, growing lots of different crops and growing perennial and annual crops alongside each other, the soil is held together and doesn’t erode. This will ultimately lead to more ‘predators’, ladybirds, hoverflies, all insects that can survive in that particular system thus reducing the need for pesticides.

“I don’t really understand why governments aren’t giving more support to that kind of [sustainable] farming but it doesn’t depend on the product of the agrochemical industry so they don’t like it and I guess that’s it. In Britain (and probably the Netherlands) we import huge amounts of fruit and vegetable from around the world even though the climate in Britain and the Netherlands is very good for growing fruit and vegetable. Instead, we choose to grow these big cash crops like wheat, most of which just end up going to animals anyways and I’ve always found that really odd and I don’t quite understand the economic process underlying that,” says Professor Goulson.

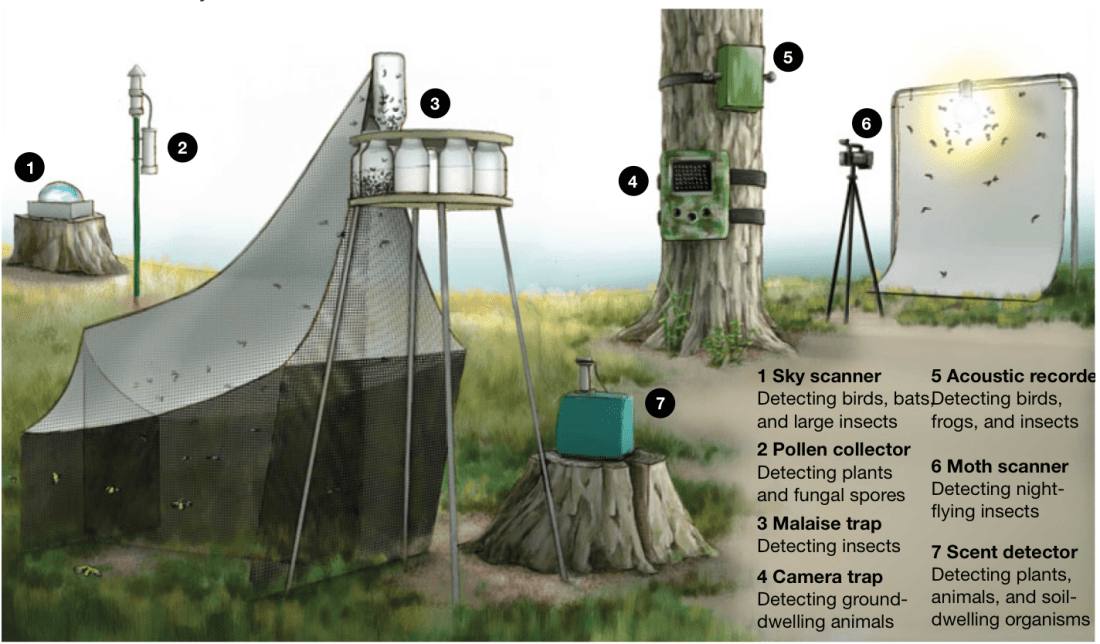

What remains agreed amongst all scientists is the implementation of effective measuring schemes for all new initiatives so as not to allow major biodiversity changes to go unnoticed again.

“There are a number of things that are complimentary that should be happening at the same time because they will enforce each other. Small-scale experiments, with powers involved, with the public involved, with local communities involved, are very important, and how long and resilient are those initiatives. It’s now very important that these initiatives are all monitored so that we really know what is making a difference regarding the protection of our environment,” says Professor Hans de Kroon.

So far this year, the German government has issued an Agri-food plan that aims to raise organic land area from 7 per cent to 20 per cent by 2030 with an added push toward conservation agriculture and plant protection. Should Germany reach this target, it will occupy 3.4 million hectares of organic farming. The new plans will also aim to phase out glyphosate (a systematic herbicide), thanks to efforts from Agriculture Minister and Svenja Schulze.

I think what we really need to do is really to invest in monitoring the German data. It’s really unique. It’s amazing what they have done and was really visionary to start a monitoring program in the late ’80s and hold on to it until this very day. It also highlights that we really need those things to see what’s going on. We are starting with new monitoring programs in homes to have a good idea of what measures really make a difference and what are, perhaps, less successful. That is so important. But what really is working, what is not, and how we can get that information back to the people who are sort of involved in all these changes,” says Professor Kroon.

He predicts that results from the initiative’s changes will become noticeable within a five year time period, particularly after the 2020 CAP reform.